Femme Fatale; Detective; Anthropologist. Artist.

Femme Fatale; Detective; Anthropologist. Artist.

Into the Conceptual Work of Sophie Calle

"I had no friends; I didn't know what to do with my life, so I started to follow people." Why? asks the journalist. "Establishing rules and following them is restful. If you follow someone, you don't have to wonder where you're going to eat. They take you to their restaurant. The choice is made for you."

—Sophie Calle (2017)

In this quote, french conceptual artist Sophie Calle, born in 1953, reminisces about her early works, which inspired her to push boundaries throughout her repertoire. Dancing between the lines of private and public, fiction and reality, with particular affinity towards narrative through photo series and texts, Sophie Calle evokes a sense of intimacy with her subjects. While in some of her modes of portrayal it might seem like she is removed from her work, and becomes a detective of sorts, merely observing the everlasting state of vulnerability humans seem to inhabit, the more “observational” her work is, the more involved she becomes. Crafting nuanced stories about her subjects, her work seems to be informed by her unapologetically sentimentalized views of the world, and takes life as an extension of her mind and vision projected in the stories of others. Although Calle employs a series of artistic mediums, predominantly photography, film, and text, the work is less focused on the formal qualities in of themselves and more focused on the conceptual qualities, using the medium as a mode of portrayal rather than for the intrinsic qualities the medium carries.

Moreover, Calle’s work is heavily informed by the literary movement Oulipo. Born in Paris in the 1960’s, the movement’s philosophy aims to create greater freedom in literature and expression by tightening its constraints. Sophie Calle echoes the movement by setting rules to her explorations of the world and her art- making a rigid game of life and an anthropological intervention. I'm not obsessive," she claims, "but I am rigorous. If I have decided that there is this rule or that rule then I am very committed. I don't get bored. I think I have an ability because I believe in the construction of the idea. If it's a good idea then it's exciting. I am interested on how it will stand on the wall." She conceptualizes a study, and then rigorously follows it, creating a method to her “madness”, and commits to following her self-induced regulations regardless of how many socially accepted boundaries these cross.

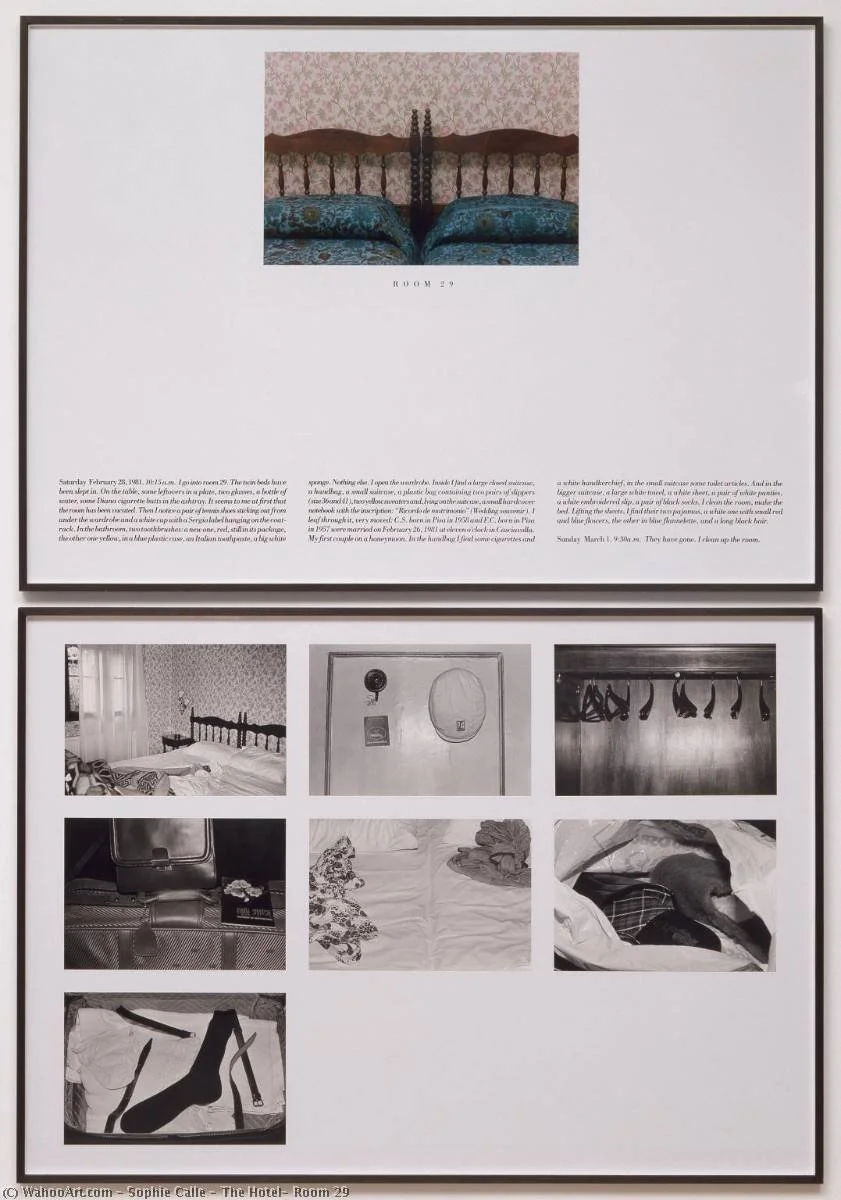

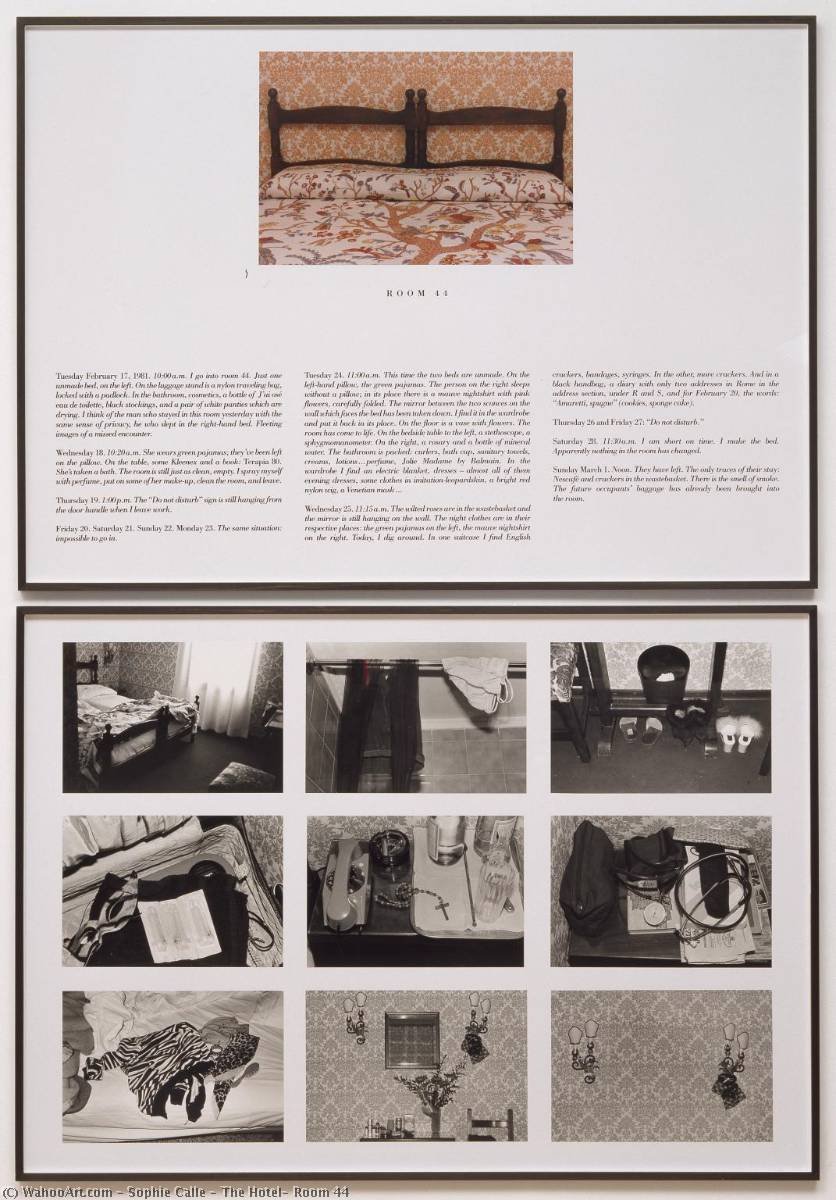

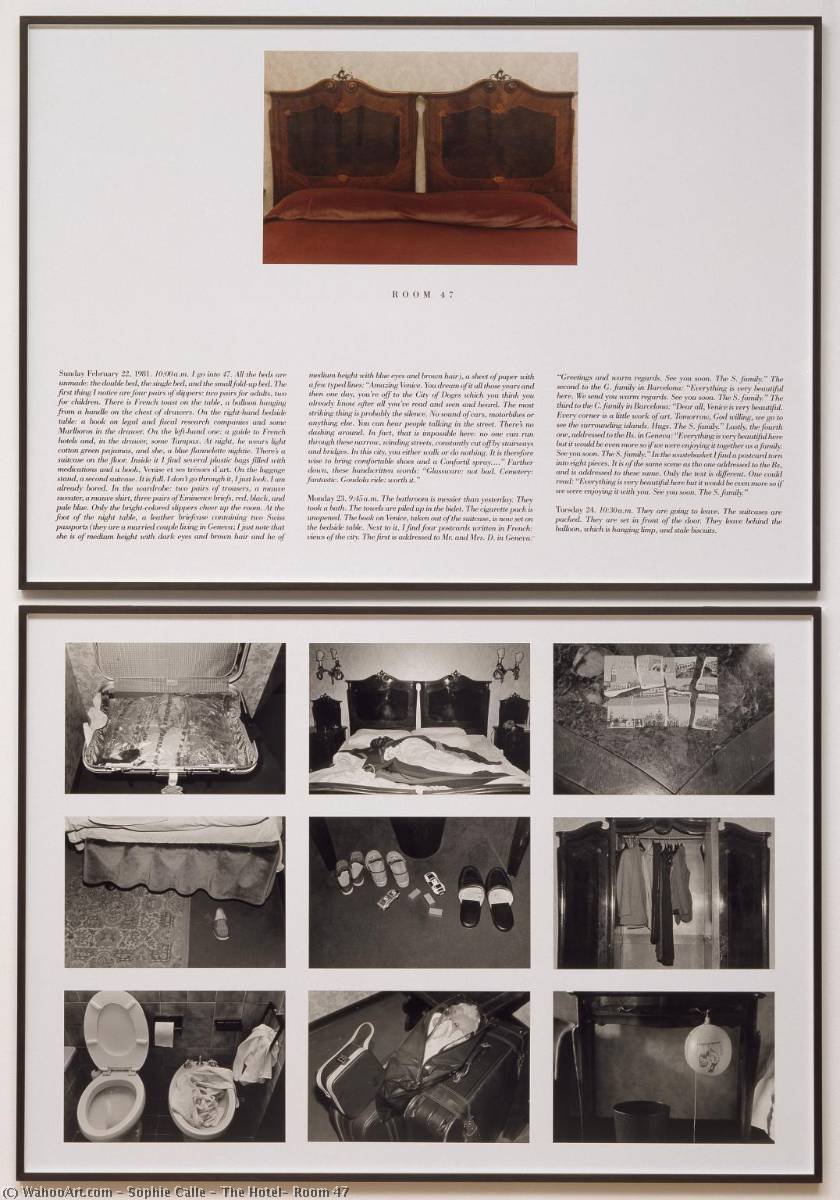

Her earlier works have a voyeuristic appeal that carry an unashamed sense of intrusion. L’ Hotel (1981), a series that features 21 diptychs arises from Calle’s three week project working as a chambermaid in Venice. She uses black and white analogue photographs to interpret the story of the lives of the hotel guests, photographing their belongings and the way they leave the room when they are not present in the hotel. She takes in-depth notes throughout their stay, continually scanning their belongings- clothes, passports, letters- anything that might reveal something about their personality or story, and even tries on their perfumes, and smells their food. She photographs in a way that a crime scene photographer would, where the subject of study, may it be slippers, a handbag, or the way they left their towels takes up the totality of the frame. Despite the lack of artistic styling, the way she emphasizes detail throughout gives life to the arrangement in the elements of what could appear at first sight as mundane due to the lack of knowledge from the guests. The more selected details she provides, the more artistic the arrangements seem, as if she is curating what objects to demonstrate in a gallery of the guests personality. She captures the presence of human subjects in a paradoxical way- their absence becomes their portrayal, providing a sense of forced intrusion and uncanny confidentiality to the audience looking at the images and texts: an nonconsensual violation of privacy that leaves the viewer wondering if they are doing something wrong by viewing the images.

Similarly, the artist brings the audience into what feels like eavesdropping in a conversation that isn't theirs, with her work “Suite Vennetiene” (1980): a book that features, quite literally, the stalking of Henri B, a man she met in Venice. Calle follows him and photographs him without his consent, writing notes that explore his every move in a romanticized, idealized way. Calle’s photographs of the man use very particular framing methods, placing him, or his back, rather, either right in the center of the frame or in one third of the frame. There is usually a divide in the foreground- a door, a column, a window- unfolding an increasing sense of urgency with every image with no resolution, until the last image of the series, that features his hand covering Calle’s lens. Still, the man is left faceless, an unresolved resolution.

Nothing quite epitomizes the game of observational cat and mouse, of blurring the lines of privacy and identity in her next work, “The Shadow” (1981) where Calle calls her mom to contract a private investigator, who follows her during the day and takes notes, oblivious to the fact that Calle is in fact observing herself through him. Simultaneously, Calle mentally takes the roll of the private investigator, observing herself as he would, and taking notes of her every move, creating simultaneous narration with her notable text descriptions, which she later presents alongside the images of the detective, that merely capture her as a dark shadow as they are taken against the light- towards the way she consistently point towards during the day. She becomes a shadow, in her shadow’s eyes- alluding to the metaphysical nature of Oulipo.

Her exploration of metaphysics, of the self, and looking through the eyes of others, or rather, looking through the perception of others becomes even more prominent during her series “The Blind (1986)”. Calle asks visually impaired individuals to describe what beauty looks like to them. She photographs their face, taking full frame of the image in an unapologetic way, and photographs her perception of what they describe- presenting both images next to each other with their quote describing beauty. Sophie Calle’s work becomes the eyes of the blind of sorts, and her work takes the form of a synesthesia very much subject to the beholder.

Calle’s conceptual work and affinity towards exploring the anthropological themes of privacy, intimacy, identity, and metaphysics push boundaries of the socially acceptable. She uses the medium of photography as merely a channel to push said boundaries and emphasize her conceptual work rather than to emphasize its formal properties or techniques. Through the placement of rigid rules she makes a game of life and the subjects of portrayal- emphasizing the very raw and very vulnerable state that prevails around every human interaction and action or inaction.

Works Cited

Duguid, Hannah. “Up Close and (Too) Personal: A Sophie Calle Retrospective.” The Independent, Independent Digital News and Media, 23 Oct. 2011, www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/up-close-and-too-personal-a-sophie-calle-retrospective-1809346.html.

Jeffries, Stuart. “Sophie Calle: Stalker, Stripper, Sleeper, Spy.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 23 Sept. 2009, www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/sep/23/sophie-calle.

Media Art Net. “Media Art Net: Calle, Sophie: L'Hotel.” Medien Kunst Netz, Media Art Net, 9 Mar. 2020, www.medienkunstnetz.de/works/hotel/.

Schilling, Mary Kaye. “The Fertile Mind of Sophie Calle.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 10 Apr. 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/04/10/t-magazine/sophie-calle-artist-cat-pregnant.html.

Tate. “'The Hotel, Room 28', Sophie Calle, 1981.” Tate, 1 Jan. 1981, www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/calle-the-hotel-room-28-p78301.